Crystal from a Rubyist’s Perspective

Crystal is a language written to be very much like Ruby but as a compiled language rather than an interpreted one. This gives us the advantage of compile time optimizations which will make our code run much faster.

Another difference in Crystal’s design is that it’s a Typed language rather than a Dynamically Typed one. This helps with the languages compilation and allows for further memory and performance optimization.

But the types don’t need to be declared at every point in your code. Crystal has been designed with Type Inference, meaning it figures out what types things are supposed to be, when it can, based on the code that uses it. This makes our jobs as developers a lot easier.

The process of discovery for me in this language started with translating a Ruby gem of mine into a Crystal shard (a shard is the same thing as a gem in that it is a way to package project code for inclusion in other projects). Next I read through the language’s available documentation. Then I built a Crystal web project on Heroku and modeled the code base after Rails. Next I got into the zone and translated the Arel code base to Crystal via Error Driven Development, which can be considered a work in progress. And finally, I wrote a recursive string parser.

This is how I learned the language. It’s the kind of practice I would recommend for learning any language that is young and still not fully mature.

The Anatomy of Crystal

One of the first things I found really attractive about Crystal’s syntax is how its method definition parameters are handled. Crystal has taken the lessons learned from other languages and improved upon them. This does add a slight learning curve, but it’s not too much.

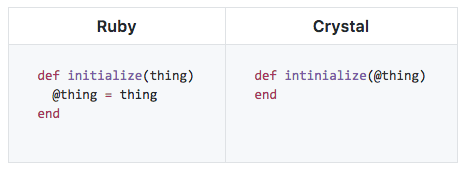

Looking at setting instance variables in an Object initializer, we’ll see Crystal has followed CoffeeScript’s way of doing it.

This does the instance variable assignment for us so we can keep a cleaner initialize code block. Another nice thing about method parameters is that all parameters can optionally be set by using keywords.

def example(a, b) puts [a, b] end example b: 1, a: 2 # [2, 1]

We also have mapping of external keyword parameters to internal local variables.

def multiply_four(by multiplier) 4 * multiplier end multiply_four by: 4 # => 16

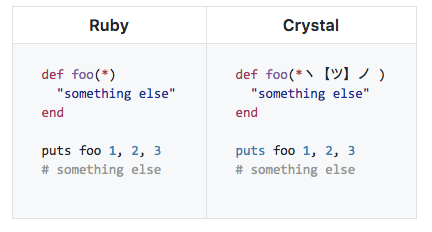

The use of * as a lone parameter has changed though. In Ruby, you can use that for methods where you don’t care about any parameters passed in to it. But Crystal uses that as a marker for declaring all the following parameters as usable by keywords alone.

Crystal requires that the splat operator * be used with a valid local variable name if you want it to consume any number of arguments. Otherwise only use it to enforce keyword arguments. Surprisingly, with all this added, Ruby’s method parameters are still compatible to Crystal.

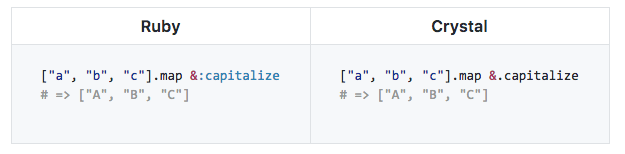

Crystal has a different syntax for symbol-to-proc method parameters; instead of &: as in Ruby, it uses &., which Ruby has created as the lazy man operator as of Ruby 2.3.

Ruby has limited this use of to_proc on symbol to only working as a method parameter. Crystal has a bit more flexibility to it.

["a","b","c"].map &.capitalize.+("Z")

# => ["AZ", "BZ", "CZ"]That’s a decent intro for now for syntax differences. Let’s get into the Rails modeling I attempted and cover what was learned in the process.

Modeling after Rails

To keep things as simple as possible, I didn’t want to reinvent any wheels. I was already reinventing the train, as it were. So I’ll start with Crystal’s Sinatra clone to get the project going.

Kemal is to Crystal what Sinatra is to Ruby. As I haven’t developed with Sinatra, this was my first exposure to something like this. But with their design principles of simplicity and minimalism, it’s pretty easy to pick it up.

Kemal puts most everything in the global namespace, which I find disturbing. I think it’s an anti-pattern to good organized code and raises the risk of intermixing code with naming conflicts. Also the code samples I’ve seen online seem to confirm that this anti-pattern is used; I’ve seen all the code clumped together in the main namespace with the different domain logic not separated out.

But after some further thinking on this, I realized Crystal’s method overloading helps prevent most name collision issues. So the issue isn’t as big of a deal as it would be in Ruby.

Method overloading

Method overloading is a feature in Crystal where you can write the same method multiple times but with different parameters passed to it. The language will properly identify which method is being called based on which parameter layout matches the types and parameters given.

def thing_one "No parameters" end def thing_one(value : Int32) "Integer parameter" end def thing_one(value : String) "String parameter" end thing_one # => "No parameters" thing_one 1 # => "Integer parameter" thing_one "hello" # => "String parameter"

Method overloading is a huge optimization for you; you don’t have to write nil checks, implement case switching, or worry about duck types. The right method for the right use case is used and compiled where it needs to be.

Organizing Toward Rails’ Design

The first thing to do is to generate a project directory.

crystal init app project

Next is to add our dependencies to shard.yml.

dependencies:

kemal:

github: kemalcr/kemal

branch: masterNext, to install the dependencies, run crystal deps. This behaves like Bundler’s bundle install command.

Requiring code

Crystal’s require keyword is different from Ruby’s in that it requires any local code to be given with a relative path starting with a dot.

# EXAMPLE require "other_shard" require "./local_file" require "./sub_directory/local_file" require "../parent_dir_file"

For requiring all files in a given directory, there are two globbing ways to accomplish this.

# All .cr files in the sub directory require "./sub/*" # All .cr files in all directories beneath sub require "./sub/**"

This is a breaking change from Ruby and doesn’t use any load path to lookup files as Ruby does (another big optimization). When porting code over to Crystal, this will be the first thing the compiler will tell you to fix.

To create a similar layout to Rails, we’ll start with one controller, one view, and a router. Open up your project’s main source file in src/ and enter the following.

# src/railslike.cr require "kemal" require "../config/**" require "../app/**" Kemal.run

Since this is a website, you won’t need to have or require a version file. We’ll place a routes.cr file in /config, base_controller.cr and index_controller.cr files in /app/controllers, and an index.ecr file in /app/views, along with a few other files we’ll mention later. ECR is Crystal’s equivalent to Ruby’s ERB, with improvements.

The routes

# config/routes.cr

require "../app/controllers/*"

module Railslike

module Routes

include Controllers

get "/", &IndexController.to_proc

end

endKemal’s routing takes a string path parameter and then a block of code to execute when that path is visited in a web request. Crystal allows a Proc to be passed as a block if you place an ampersand, &, before it. The to_proc method is one we define ourselves on BaseController.

The controllers

We’ll start with BaseController, which other controllers will inherit from.

require "ecr/macros"

module Railslike

module Controllers

abstract class BaseController

def initialize(@env : HTTP::Server::Context); end

def render(instance : BaseController)

LayoutController.new(env, instance).render

end

def self.to_proc

->(env : HTTP::Server::Context){

# Instantiate new Controller/View

controller = new(env)

# Render own view through application template

controller.render(controller)

}

end

def name

self.class.name.split("::").last

end

ECR.def_to_s \

"#{`pwd`.chomp}/app/views/" +

@type.name.id.

split("::").last.

split("Controller").first.

downcase +

".ecr"

macro inherited

def content; self.to_s end

end

private getter :env

end

end

endThere’s quite a bit going on here, so let’s start from the entry point. From our routes file, we call to_proc; here we have a proc to create an instance of the current class and pass through the env that Kemal pipes in from the get request.

The env is an instance of HTTP::Server::Context that contains all the information that’s available from the request. You can see that we set the instance variable for this with @env in the initialize method.

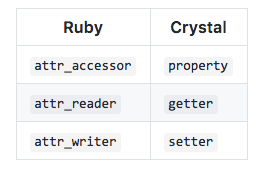

Crystal has alternatives for Ruby’s attr methods:

At the end of the class, we define a private getter. This way, the instance of this controller generated will have access to the env data returned from within any method.

The ECR.def_to_s is a macro function written for Crystal’s templating language ECR. We’ll discuss macros shortly. This macro method is written to digest the template file into code and write a to_s method in the current scope so that your view is a simple method call.

Since this is a class to be inherited, we are making it an abstract class. This will allow us to use BaseController as a type on any other controller that inherits it.

For example, the render method written above has its parameter type set as BaseController. This works with any object that is a “kind of” BaseController because we made it abstract. You can also define methods as abstract if you’re defining an API.

The macro inherited is Crystal’s alternative to def self.inherited(base) and may require that the class its written in be abstract. We’re defining the method content on any controller that inherits this class, since the application template will be rendering the content method as the main content of the page.

Macro limitation

When you write macros, you are only using a very small subset of the language, so you are limited in ways to accomplish things. You can read the methods available to you for writing macros in the macro method source.

For example, the ECR.def_to_s macro used in the code above needed to use absolute file paths to get the view to parse (the relation of where your executable is run from matters). The code normally available for printing the working directory FileUtils.pwd was not available, so I executed the system’s pwd command with backticks. Since Crystal currently only works on Linux and Mac, I know that the pwd command will be available.

Next you’ll notice complex regex text filtering wasn’t available to me. I used the split method as a substitute to remove the text I didn’t want in the string. The fancy string substitution we’ve done is to take the controller name and use it for the name of the file for the view. So IndexController gets mapped to the file app/views/index.ecr.

Currently, Kemal has a render macro defined that can accept an application template. However, it doesn’t permit the dynamic file naming we’re using here (as of this writing), so we’ll write our own application template renderer.

The application layout

The controller

# app/controllers/layout_controller.cr

require "ecr/macros"

module Railslike

module Controllers

class LayoutController

def initialize(@env : HTTP::Server::Context, @inner_context : BaseController); end

def render

to_s

end

ECR.def_to_s "#{`pwd`.chomp}/app/views/layout.ecr"

forward_missing_to inner_context

private getter inner_context

private def css_asset(file = "application.css")

"/stylesheets/#{file}"

end

private def js_asset(file = "application.js")

"/javascripts/#{file}"

end

end

end

endThe application template

This layout controller defines our assets path for the view, pulls in the template, and defines a to_s method. Since we call render on it from the BaseController.render method, it runs the to_s in this template, which in itself calls the context method of the view for whatever page we’re on to load it. This happens by the forward_missing_to macro to make all of the context of the inner controller/view available to us.

To make the assets work, we need to define an application configuration and set it in Kemal.

# config/application.cr Kemal.config do |config| config.public_folder = "./app/assets/" end

Seeing It Work

IndexController

# app/controllers/index_controller.cr

require "./base_controller"

module Railslike

module Controllers

class IndexController < BaseController

end

end

endThe view

Make sure you create the files app/assets/javascripts/application.js and app/assets/stylesheets/application.css and add anything you’d like to see in the results.

If you haven’t already, be sure to run crystal deps to install dependencies. Then build the application with crystal build src/railslike.cr. It will create an executable in the current directory name railslike. Go ahead and run that, and the site will be visible in your browser at http://localhost:3000.

If any errors occur, you will have a verbose output to help you in your browser. This is because it was compiled without a --release flag. It will compile faster without it and give you more helpful debugging messages.

For the working source code version of this code, you can see my GitHub repo on it: danielpclark/crystal-rails-template. There is a 404 error controller added in this code base as well to help.

Helpful tip: env.params.query is a hash-like object for incoming web request parameters.

Closing Tips

The Crystal language is still very young and volatile. What I mean by volatile is that the language itself has many changes in its design yet to come that aren’t backwards compatible.

This can be witnessed by looking at the project Frost, which is meant to be the Rails of the Crystal language. Development on it ceased about a year ago and it no longer works with current Crystal versions; just updating it to work for one minor version change is tedious, let alone six of them.

What does this mean for us? I believe it’s a caution as to how we go about implementing our projects in Crystal while it’s still young. If we can identify the areas that have the least risk of change and implement our code base on that, then we improve the longevity of our code base.

There are added keywords/macros to the language that may be surprising. For instance, select is taken and can’t be used as a local variable, as macros and keywords take precedence over local variables. This method is a feature currently being implemented to allow Go-like threading to the language.

Some gotchas coming from Ruby:

- Methods ending with

=can’t take splat operators. - Parentheses are mandatory on method definitions but not method calls. (No Seattle.rb style)

- There is NO introspection whatsoever, which makes reading the source code crucial.

- Symbols are fixed at compile time and can’t be generated dynamically.

- In testing, instead of using

let, define methods asprivateand the private method will remain scoped to the current test file alone. privatemust be defined before each method or class and does not act as a change for the lexical scope.- Strings need to use double quotes.

Type Inference is nice but the compiler doesn’t always get it right. You can specify type for the output on methods by declaring them after the closing parentheses. This can save you a lot of time!

def testing(val : Int32?) : Hash(String, Nil) | Hash(String, Int32)

v = rand(val || 0)

if v >= 2

{"val" => 42}

else

{"val" => val}

end

endYou may experiment with Crystal code on the Crystal Playground.

Summary

Crystal offers orders of magnitude of performance benefits. Instead of measuring performance in hundreds of seconds, you’ll be counting it in hundreds of microseconds µs. This makes for a more desirable choice for a web API endpoint.

Since Crystal is mostly like Ruby, you get the added benefit of being nearly as productive as you would be while developing in Ruby with a much more performant end result. I say nearly because simple designs can be implemented without any extra cost; however, as the language has no introspection and is lacking in documentation, getting into more complex issues will cost more than planned.

Would I recommend Crystal for an API? Undoubtedly yes. Just be sure to take into account the cost of the ever-evolving language.

The core team for Crystal’s development is super helpful should you have any questions. Be sure to ask questions on Stack Overflow if you need to. Their developers are very active in answering questions. I have found their help to be quite the blessing in learning Crystal.

In my humble opinion, the benefits of Crystal far outweigh the costs. I recommend anyone already familiar with Ruby or CoffeeScript to get started on it. As it has no introspection and lacks in documentation, I would recommend that others become familiar with the syntax through Ruby first. It really is quite rewarding being able to release a fast executable program for others to use!

| Reference: | Crystal from a Rubyist’s Perspective from our WCG partner Daniel P. Clark at the Codeship Blog blog. |