Microservice Communication with Queues

Microservices are small programs that handle one task. A microservice that is never used is useless though — it’s the system on the whole that provides value to the user. Microservices work together by communicating messages back and forth so that they can accomplish the larger task.

Communication is key, but there are a variety of ways this can be accomplished. A pretty standard way is through a RESTful API, passing JSON back and forth over HTTP. In one sense, this is great; it’s a form of communication that’s well understood. However, this method isn’t without flaws because it adds other factors, such as HTTP status codes and receiving/parsing requests and responses.

What other ways might microservices communicate back and forth? In this article, we’re going to explore the use of a queue, more specifically RabbitMQ.

What Does RabbitMQ Do?

RabbitMQ provides a language-agnostic way for programs to send messages to each other. In simple terms, it allows a “Publisher/Producer” to send a message and allows for a “Consumer” to listen for those messages.

In one of its simpler models, it resembles what many Rails developers are used to with Sidekiq: the ability to distribute asynchronous tasks among one or more workers. Sidekiq is one of the first things I install on all my Rails projects. I don’t think RabbitMQ would necessarily take its place, especially for things that work more easily within a Rails environment: sending emails, interacting with Rails models, etc.

It doesn’t stop there though. RabbitMQ can also handle Pub/Sub functionality, where a single “event” can be published and one or more consumers can subscribe to that event. You can take this further where consumers can subscribe only to specific events and/or events that match the pattern they’re watching for.

Finally, RabbitMQ can allow for RPCs (Remote Procedure Calls), where you’re looking for an answer right away from another program… basically calling a function that exists in another program.

In this article, we’ll be taking a look at both the “Topic” or pattern-based Pub/Sub approach, as well as how an RPC can be accomplished.

Event-based and asynchronous

The first example we’ll be working with today is a sports news provider who receives incoming data about scores, goals, players, teams, etc. It has to parse the data, store it, and perform various tasks depending on the incoming data.

To make things a little clearer, let’s imagine that, in one of the incoming data streams, we’ll be notified about soccer goals.

When we discover that a goal has happened, there are a number of things that we need to do:

- Parse and normalize the information

- Store the details locally

- Update the “box-score” for the game that the goal took place in

- Update the league leaderboard showing who the top goal scorer is

- Notify all subscribers (push notification) of a particular league, team, or player

- And any number of other tasks or analysis that we need to do

Do we need to do all of those tasks in order? Should the program in charge of processing incoming data need to know about all of these tasks and how to accomplish them? I suggest that other than parsing/normalizing the incoming data and maybe even saving it locally, the rest of the tasks can be done asynchronously and that the program shouldn’t really know or care about all of these other tasks.

What we can do is have the parser program emit an event (soccer.mls.goal for example), along with its accompanying information:

{

league: 'MLS',

team: 'Toronto FC',

player: 'Sebastian Giovinco',

opponent: 'New York City FC',

time: '14:21'

}The parser can then forget about it! It’s done its work of emitting the event. The rest of the work will be done by any number of consumers who have subscribed to this specific event.

Producing in Ruby

To produce or emit events in Ruby, the first thing we need to do is install the bunny client, which allows Ruby to communicate with RabbitMQ. For an example, here is some fake incoming data that needs to trigger the goal event for soccer.

# Imagine the parsing happens here :) soccer = Soccer.new soccer.emit_goal( league: 'MLS', team: 'Toronto FC', player: 'Sebastian Giovinco', opponent: 'New York City FC', time: '14:21' )

Let’s next take a look at the emit_goal function inside of the Soccer class, which builds the event slug and packages the data together to be included in the event being emitted:

class Soccer

include EventEmitter

def emit_goal(raw_details)

slug = "soccer.#{raw_details[:league]}.goal".downcase # "soccer.mls.goal"

payload = raw_details.slice(:league, :team, :player, :opponent, :time)

emit('live_events', slug, payload)

end

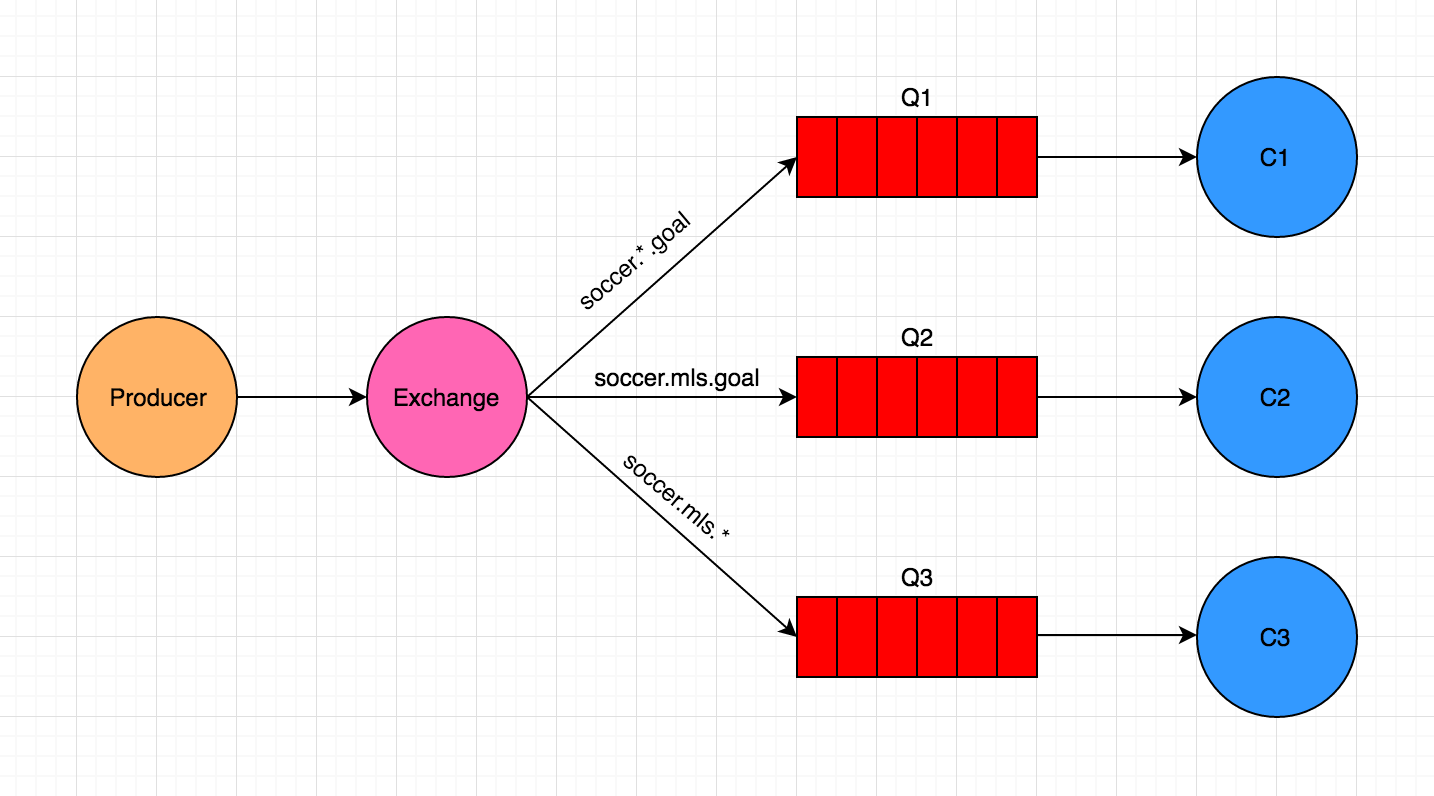

endThe 'live_events' string has to do with which Exchange to publish the event to. An Exchange is basically like a router that decides which Queue(s) the event should be placed into. The emit method is inside of a Module I created to simplify emitting events:

module EventEmitter

def emit(topic, slug, payload)

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.topic(topic)

x.publish(payload.to_json, routing_key: slug)

puts " [OUT] #{slug}:#{payload}"

conn.close

end

endIt receives the topic, event slug, and event payload and sends that information to RabbitMQ.

Consuming in Ruby

So far we have produced an event, but without a consumer to consume it, the event will be lost. Let’s create a Ruby consumer that is listening for all soccer goal events.

You may have noticed that what I was calling the event slug (or the routing_key) looked like "soccer.mls.goal". Picking a pattern to follow is important, because consumers can choose which events to listen for based on a pattern such as "soccer.*.goal": all soccer goals regardless of the league.

The consumer in this case will be some code which updates the leaderboard for the top goal scorers in the league. It is kicked off by running a Ruby file with this line:

SoccerLeaderboard.new.live_updates

The SoccerLeaderboard class has a method called live_updates which will call a receive method provided be an included Module. It will provide the topic, the pattern of event slug/routing_key to listen for, and a block of code to be called any time there is a new event to process.

class SoccerLeaderboard

include EventReceiver

def live_updates

receive('live_events', 'soccer.*.goal') do |payload|

puts "#{payload['player']} has scored a new goal."

end

end

endThe EventReceiver Module is a little larger, but for the most part it’s just setting up a connection to RabbitMQ and telling it what it wants to listen for.

module EventReceiver

def receive(topic, pattern, █)

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.topic(topic)

q = ch.queue("", exclusive: true)

q.bind(x, routing_key: pattern)

puts " [INFO] Waiting for events. To exit press CTRL+C"

begin

q.subscribe(:block => true) do |delivery_info, properties, body|

puts " [IN] #{delivery_info.routing_key}:#{body}"

block.call(JSON.parse(body))

end

rescue Interrupt => _

ch.close

conn.close

end

end

endConsuming in Elixir

I mentioned that RabbitMQ is language agnostic. What I mean by this is that we can not only have a consumer in Ruby listening for events, but we can have a consumer in Elixir listening for events at the same time.

In Elixir, the package I used to connect to RabbitMQ was amqp. One gotcha was that it relies on amqp_client which was giving me problems with Erlang 19. To solve that, I had to link directly to the GitHub repository because it doesn’t appear that the fix has been published to Hex yet.

defp deps do

[

{:amqp_client, git: "https://github.com/dsrosario/amqp_client.git", branch: "erlang_otp_19", override: true},

{:amqp, "~> 0.1.5"}

]

endThe code to listen for events in Elixir looks like the following code below. Most of the code inside of the start_listening method is just creating a connection to RabbitMQ and telling it what to subscribe to. The wait_for_messages is where the event processing takes place.

defmodule GoalNotifications do

def start_listening do

{:ok, connection} = AMQP.Connection.open

{:ok, channel} = AMQP.Channel.open(connection)

AMQP.Exchange.declare(channel, "live_events", :topic)

{:ok, %{queue: queue_name}} = AMQP.Queue.declare(channel, "", exclusive: true)

AMQP.Queue.bind(channel, queue_name, "live_events", routing_key: "*.*.goal")

AMQP.Basic.consume(channel, queue_name, nil, no_ack: true)

IO.puts " [INFO] Waiting for messages. To exit press CTRL+C, CTRL+C"

wait_for_messages(channel)

end

def wait_for_messages(channel) do

receive do

{:basic_deliver, payload, meta} ->

IO.puts " [x] Received [#{meta.routing_key}] #{payload}"

wait_for_messages(channel)

end

end

end

GoalNotifications.start_listeningRPC… when you need an answer right away

Remote Procedure Calls can be accomplished with RabbitMQ, but I’ll be honest: It’s more involved than the examples above for more of a typical Pub/Sub approach. To me, it felt like each side (producer/consumer) has to act as both a producer and a consumer.

The flow is a little like this:

- Program A asks Program B for some information, providing a unique ID for the request

- Program A listens for responses that match the same unique ID

- Program B receives request, does the work and provides a response with the same unique ID

- Program A runs callback once matching unique ID is found in response from Program B

In this example, we’ll be talking about a product’s inventory… an answer we need to know right away to be sure that there is stock available for a customer to purchase.

inventory = ProductInventory.new('abc123').inventory

puts "Product has inventory of #{inventory}"The ProductInventory class is quite simple, mostly because I’ve hidden the complexity of the RPC call inside of a class called RemoteCall.

class ProductInventory

attr_accessor :product_sku

def initialize(product_sku)

@product_sku = product_sku

end

def inventory

RemoteCall.new('inventory').response(product_sku)

end

endNow let’s take a look at how RemoteCall is handling it:

require 'bunny'

require 'securerandom'

class RemoteCall

attr_reader :lock, :condition

attr_accessor :conn, :channel, :exchange, :reply_queue,

:remote_response, :call_id, :queue_name

def initialize(queue_name)

@queue_name = queue_name

@conn = Bunny.new

@conn.start

@channel = conn.create_channel

@exchange = channel.default_exchange

@reply_queue = channel.queue('', exclusive: true)

end

def response(payload)

@lock = Mutex.new

@condition = ConditionVariable.new

response_callback(reply_queue)

self.call_id = SecureRandom.uuid

puts "Awaiting call with correlation ID #{call_id}"

exchange.publish(payload,

routing_key: queue_name,

correlation_id: call_id,

reply_to: reply_queue.name

)

lock.synchronize { condition.wait(lock) }

remote_response

end

private

def response_callback(reply_queue)

that = self

reply_queue.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

if properties[:correlation_id] == that.call_id

that.remote_response = payload

that.lock.synchronize { that.condition.signal }

end

end

end

endSo if all that code was for the Producer, what does the Consumer look like? It’s kicked off with:

server = InventoryServer.new server.start

And the InventoryServer looks like:

require 'bunny'

class InventoryServer

QUEUE_NAME = 'inventory'.freeze

attr_reader :conn

def initialize

@conn = Bunny.new

end

def start

conn.start

channel = conn.create_channel

queue = channel.queue(QUEUE_NAME)

exchange = channel.default_exchange

subscribe(queue, exchange)

rescue Interrupt => _

channel.close

conn.close

end

def subscribe(queue, exchange)

puts "Listening for inventory calls"

queue.subscribe(block: true) do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "Received call with correlation ID #{properties.correlation_id}"

product_sku = payload

response = self.class.inventory(product_sku)

exchange.publish(response.to_s,

routing_key: properties.reply_to,

correlation_id: properties.correlation_id

)

end

end

def self.inventory(product_sku)

42

end

endWow… that’s a lot of work to make an RPC! RabbitMQ has a great guide explaining how this works in a variety of different languages.

Conclusion

Microservices don’t always need to communicate synchronously, and they don’t always need to communicate over HTTP/JSON either. They can, but next time you’re thinking about how they should speak to each other, why not consider doing it asynchronously using RabbitM? It comes with a great interface for monitoring the activity of the queue and has fantastic client support in a variety of popular languages. It’s fast, reliable, and scalable.

Microservices aren’t free though… I think it’s worthwhile considering whether the extra complexity involved in setting up separate services and providing them a way to communicate couldn’t be better handled using something like Sidekiq and writing clean, modular code.

| Reference: | Microservice Communication with Queues from our WCG partner Leigh Halliday at the Codeship Blog blog. |