Refactoring Legacy Rails Controllers

Ruby on Rails controllers are like the bouncers of a nightclub. No identification at a club? You aren’t getting in. Without the proper clothes, you can expect to be turned away. Oh, you wanna say something slick? You’re definitely not getting in, and you might be getting a beatdown on your way out.

Controllers are the bouncers of the Rails software stack. You aren’t logged in? See ya. You aren’t authorized to view that resource? Goodbye. Oh, you’re trying to change an attribute that you don’t have access to? You’re gone, and your account is probably getting banned too.

Controllers Rule Everything Around Me

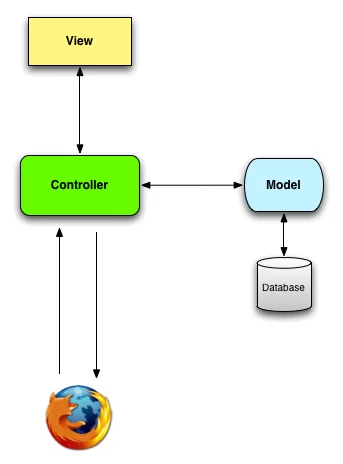

They say the eyes are the window to the soul. Controllers are the window to the soul of your application data. All requests start at the router and ultimately must pass through your controllers to get access to the data and the views.

Controllers wear many hats. They are responsible for:

- Authenticating users

- Authorizing user access to resources

- Sanitizing data input from the user

- Loading data from the models

- Rendering the view

Controllers wield massive power in a Rails application. Because controllers are so omnipotent, it’s incredibly easy for a novice programmer to bloat a controller with business logic.

Controllers Can’t Be Unit Tested

By their very nature, controllers integrate and connect multiple areas of your application. This makes controllers non-unit testable. Any time you find yourself in a controller action, you began your journey in the router. Once you’re inside the controller, a model is typically loaded and a view is rendered. The most basic Rails controllers do all of these things.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | class PostsController < ApplicationController def new @post = Post.new end def create @post = Post.new(post_params) if @post.save redirect_to @post else render :new end end private def post_params params.require(:post).permit(:title, :body, :author) endend |

Controllers Breed Bad Code

Due to their massive responsibility, controllers are highly susceptible to code bloat. They are difficult to test because they integrate multiple areas of the application. This makes controllers the ideal breeding ground for untested, spaghetti code.

The most basic controller #create actions require at least six lines of code. We must be vigilant about keeping our controller methods small and passing business logic responsibility down to the models or plain Ruby objects. When we force business logic down and out of our controllers, we gain the benefit of being able to unit test application logic. Our code consequently becomes easier to understand.

Legacy Ruby code is a nightmare

Legacy code is just the fancy way of saying untested code. Untested Ruby code is a nightmare. Ruby offers no variable type safety. As Ruby is an interpreted language, you get no compiler safety. The entire Ruby standard library can be overwritten with monkey patches. Without tests, you have no assurances that your code changes won’t break the entire application.

The first step in the battle against bloated controllers will always be to get the legacy code under test.

As we’ve already discussed, it’s incredibly difficult to test business logic that lives in the controller. Strap up, because that’s what we have to do. I’ll warn you in advance: Your controller tests will end up very large. Don’t worry, because it’s only a temporary condition. Here’s our blueprint for wrangling legacy controller code:

- Wrap controller code with pending tests to gain understanding.

- Write out the tests. Let test failures guide you to green tests.

- When you have full coverage, refactor aggressively down to the models or extract plain Ruby objects.

- Refactor your controller integration tests into unit tests.

Let’s Refactor!

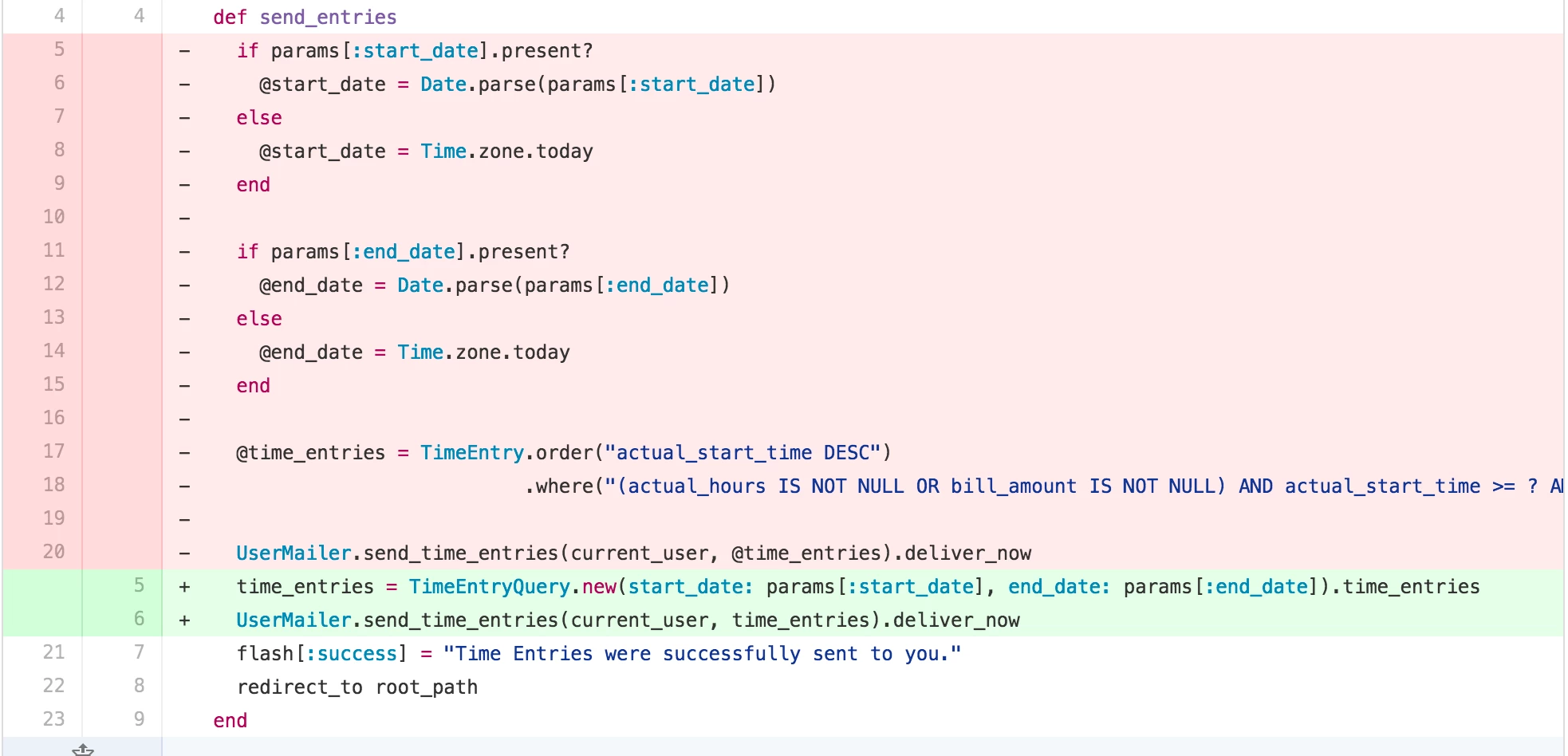

This code comes from a real project that I’ve worked on. I’ve greatly simplified the controller action to its most essential pieces. It was originally over 100 lines! The refactoring concepts discussed in this article scale all the way up to the toughest refactors.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | class TimeEntriesController < ApplicationController before_filter :authenticate_user! def send_entries if params[:start_date].present? @start_date = Date.parse(params[:start_date]) else @start_date = Time.zone.today end if params[:end_date].present? @end_date = Date.parse(params[:end_date]) else @end_date = Time.zone.today end @time_entries = TimeEntry.order("actual_start_time DESC") .where("(actual_hours IS NOT NULL OR bill_amount IS NOT NULL) AND actual_start_time >= ? AND actual_start_time <= ?", @start_date.beginning_of_day, @end_date.end_of_day) UserMailer.send_time_entries(current_user, @time_entries).deliver_now flash[:success] = "Time Entries were successfully sent to you." redirect_to root_path endend |

The controller is using #deliver_now, which sends the time entries email within the web request. This can take up to five seconds. Our goal is to port the email send-out to a background job.

In Rails 4.2+, you can background the sending of emails with the #deliver_later method. Our task is to change the deliver_now over to a deliver_later.

Let’s just change the method over right now. Maybe we don’t need to refactor at all.

1 | UserMailer.send_time_entries(current_user, @time_entries).deliver_later |

#deliver_later queues up the email with Rails’ Active Job library. Active Job serializes Active Record objects down to simple strings. When the job is activated later, Active Job can just read the attributes of your object from the string.

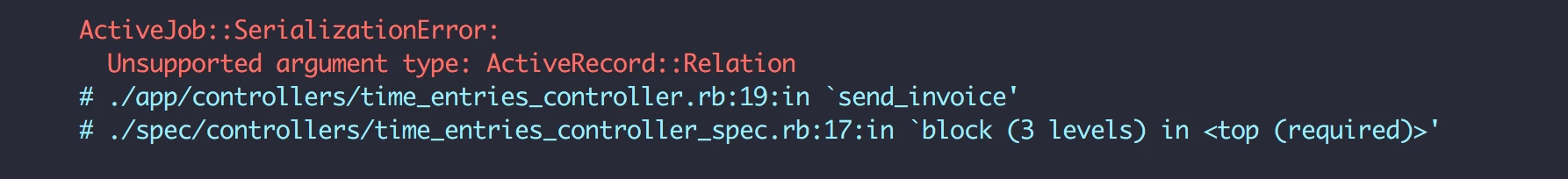

The problem with this code is that Active Job does not support serializing collections of Active Record objects. The @time_entries instance variable is populated with a collection of TimeEntry objects.

1 2 | @time_entries = TimeEntry.order("actual_start_time DESC") .where("(actual_hours IS NOT NULL OR bill_amount IS NOT NULL) AND actual_start_time >= ? AND actual_start_time <= ?", @start_date.beginning_of_day, @end_date.end_of_day) |

When you try to serialize an Active Record collection, you get the following error:

The error is telling us that we need to perform the TimeEntry query inside of the background job, instead of passing @time_entries to the mailer. That means we need all the information to recreate the query inside of the mailer, i.e., the parameters from the controller.

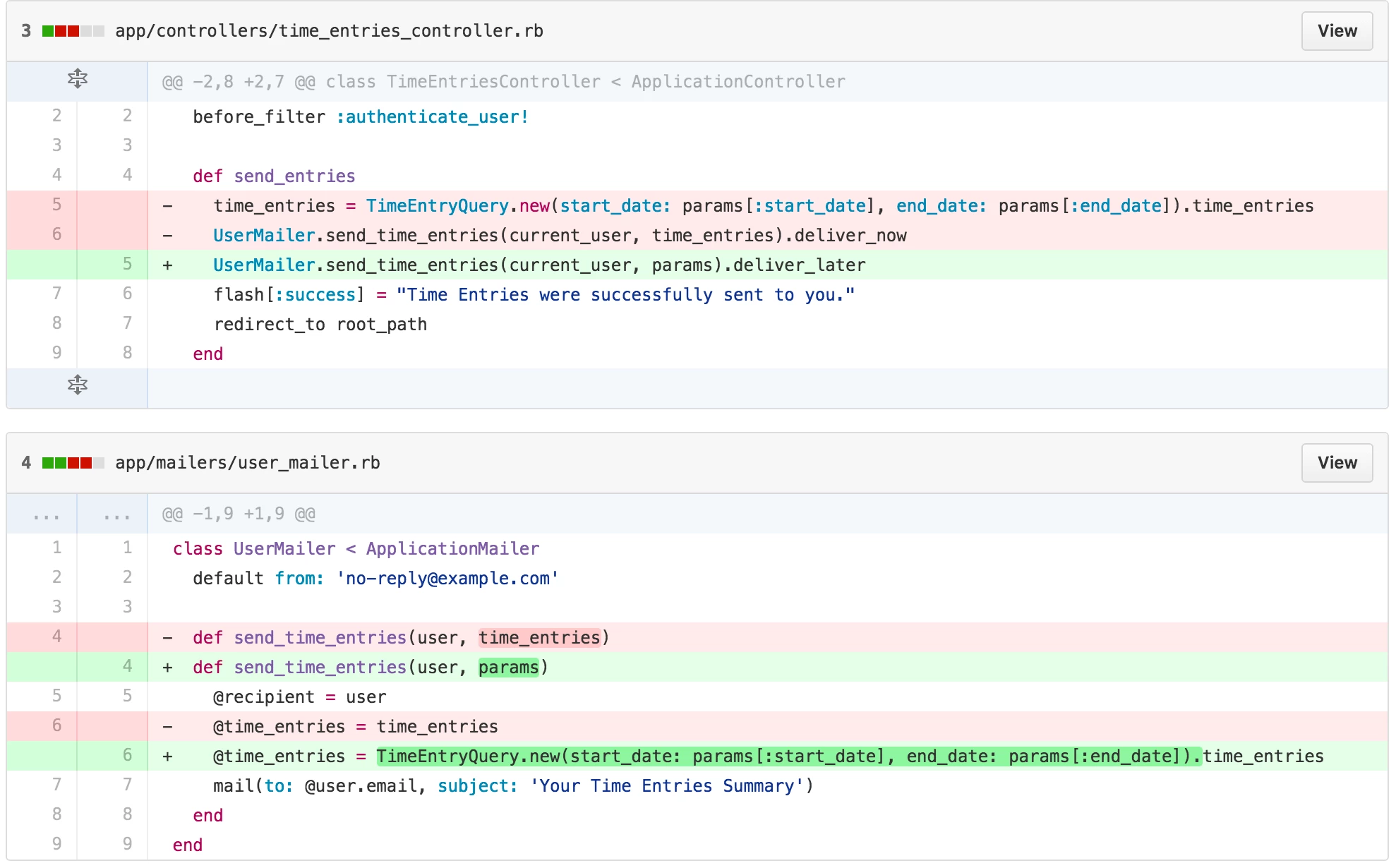

We could make this code work right now by passing the parameters down to the mailer method and performing all the query logic inside of the mailer. Here’s the mailer before we make our changes:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | class UserMailer < ApplicationMailer default from: 'no-reply@example.com' def send_time_entries(user, time_entries) @recipient = user @time_entries = time_entries mail(to: @user.email, subject: 'Your Time Entries Summary') endend |

Here’s how the mailer method expands if we choose to not refactor:

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | class UserMailer < ApplicationMailer default from: 'no-reply@example.com' def send_time_entries(user, params) @recipient = user if params[:start_date].present? @start_date = Date.parse(params[:start_date]) else @start_date = Time.zone.today end if params[:end_date].present? @end_date = Date.parse(params[:end_date]) else @end_date = Time.zone.today end @time_entries = TimeEntry.order("actual_start_time DESC") .where("(actual_hours IS NOT NULL OR bill_amount IS NOT NULL) AND actual_start_time >= ? AND actual_start_time <= ?", start_date.beginning_of_day, end_date.end_of_day) mail(to: @user.email, subject: 'Your Time Entries Summary') endend |

With the above code transfer, we’ve achieved our task of being able to background the email. Since you are just passing a single Active Record object (user) and a Ruby hash (params), Active Job won’t complain about being unable to serialize an Active Record collection.

The question we should be asking is, “Why don’t we just do that and call it a day?”

The answer is because the mailer shouldn’t need to know how to construct a query. If we ever need to change how the query works or if we need to change the TimeEntry model attributes, we have to go into a mailer class and change email code.

Doesn’t that sound ridiculous?

Because the query logic is embedded inside of the mailer, we have no way to reuse that query code. We can’t call UserMailer#send_time_entries from other areas in our codebase because it’s directly coupled with sending out an email.

If we ever need to make that same query in a view or anywhere else, we’d have to copy and paste the code. If the query needs an update, it’ll need to be updated in multiple places. This is a disastrous approach to software development. Refactoring the query is our best option.

The Discovery Phase

Wrap controller code with pending tests to gain understanding.

We have to surround the controller action with a blanket of tests so that we can refactor safely.

Since it’s code that we don’t understand, the goal of our pending tests is to document all of the paths through the code. Code paths are created by conditionals.

The most common way to fork a path through code is with conditionals: if, unless, else, elsif, ? :(ternary operator), and case. Conditional expressions can be combined with || and &&.

Any time you come across a conditional, there needs to be a test. Any time you come across an area where a conditional is combined, you need an additional test.

Essentially, our tests are going to document all of the conditionals in our controller method. Start at the top of the method and work your way down through the conditionals.

This is the most critical step of our refactoring process. All of the other steps depend on nailing the Discovery Phase.

In our controller, we have two conditionals, two if-else statements. There are two paths through an if-else statement, so we’ll need four tests to document the if-else code paths.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | class TimeEntriesController < ApplicationController before_filter :authenticate_user! def send_entries if params[:start_date].present? @start_date = Date.parse(params[:start_date]) else @start_date = Time.zone.today end if params[:end_date].present? @end_date = Date.parse(params[:end_date]) else @end_date = Time.zone.today end @time_entries = TimeEntry.order("actual_start_time DESC") .where("(actual_hours IS NOT NULL OR bill_amount IS NOT NULL) AND actual_start_time >= ? AND actual_start_time <= ?", @start_date.beginning_of_day, @end_date.end_of_day) UserMailer.send_time_entries(current_user, @time_entries).deliver_now flash[:success] = "Time Entries were successfully sent to you." redirect_to root_path endend |

The first if statement is checking if the :start_date param is present. Our pending tests start off looking like this:

1 2 | context 'start date is present' context 'start date is not present' |

Despite whatever happens in the first if statement, the code will always pass through the second if statement. The second if statement checks the presence of the :end_date param. Under each :start_date context, we’ll need a context for the two :end_date conditions, present and not present.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | context 'start date is present' context 'end date is present' context 'end date is not present'context 'start date is not present' context 'end date is present' context 'end date is not present' |

We’ve accounted for the conditionals in our controller. Regardless of our path through the conditionals, three things always happen in our controller action:

- An email is always sent.

- A success message is always flashed to the user.

- The user always gets redirected to the

root_path.

Let’s add pending tests for these three events.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 | it 'delivers an email'it 'flashes a success message'it 'redirects to root path'context 'start date is present' context 'end date is present' context 'end date is not present'context 'start date is not present' context 'end date is present' context 'end date is not present' |

Finally, we need to document what we’re expecting the code to do when the :end_date and :start_date params are present/not present.

Looking at the controller, the date parameters control which time entries get returned from the TimeEntry query.

1 2 | @time_entries = TimeEntry.order("actual_start_time DESC") .where("(actual_hours IS NOT NULL OR bill_amount IS NOT NULL) AND actual_start_time >= ? AND actual_start_time <= ?", @start_date.beginning_of_day, @end_date.end_of_day) |

If we have a :start_date and we have an :end_date, then we’ll get time entries that started between those two parameters. We’ll add a pending test for that.

1 2 3 | context 'start date is present' context 'end date is present' it 'sends entries between start date and end date' |

We’ve gone line by line and discovered what the code is trying to accomplish with the date parameters. Let’s add the tests for the rest of the contexts.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 | context 'start date is present' context 'end date is present' it 'sends entries between start date and end date' context 'end date is not present' it 'sends entries between start date and today'context 'start date is not present' context 'end date is present' it 'sends entries between today and end date' context 'end date is not present' it 'sends entries only from today' |

Congratulations, we’ve now documented everything that happens in the controller action!

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | describe TimeEntriesController do describe '#send_entries' do it 'delivers an email' it 'flashes a success message' it 'redirects to root path' context 'start date is present' context 'end date is present' it 'sends entries between start date and end date' context 'end date is not present' it 'sends entries between start date and today' context 'start date is not present' context 'end date is present' it 'sends entries between today and end date' context 'end date is not present' it 'sends entries only from today' endend |

By documenting what we expect from the code, we’ve gained a maximum understanding of what the previously foreign code is supposed to accomplish. Now we can start filling out the tests!

The Bootstrapping Phase

Write out the tests. Let test failures guide you to green tests.

We are clueless about this codebase. To get these tests running, we’ll need to create objects that we know nothing about. Errors will be our best friend in the bootstrapping phase. They will guide us to creating the objects we need to set up our tests.

We’ll start with the most fundamental test, the delivering of the email.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | describe '#send_entries' do it 'delivers an email' do time_entry = TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: Time.current) post :send_invoice last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description endend |

The most basic email delivery occurs with no parameters. Looking at our pending tests, if there is no :start_date or :end_date param, only time entries from today are sent out. That leads us to write the first two lines, creating a time entry from today and invoking the controller action.

1 2 | time_entry = TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: Time.current)post :send_invoice |

We need to make sure that the time entry is included in the email, allowing us to finish the skeleton of our test.

1 2 3 4 | ...last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.lastexpect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description |

Running this code will throw errors, alerting us to what objects are necessary to get the test running.

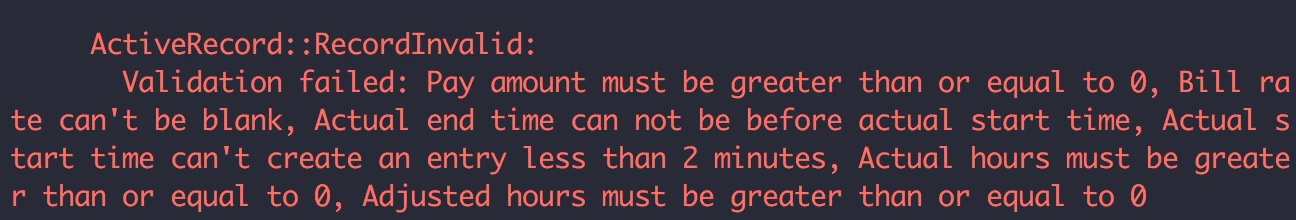

After running the test for the first time, the code complains about validation errors on the time entry.

Reading through the errors, let’s do the simplest thing to make one of the errors go away. We’ll add an actual_end_time to the time entry.

1 | time_entry = TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: Time.current, actual_end_time: Time.current + 2.minutes) |

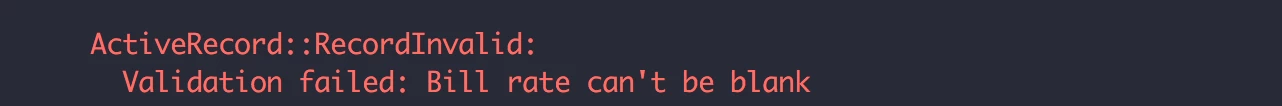

We run the tests again. It now complains about a missing attribute.

We jump into the model, and the only way to make that bill rate validation go away is to create a Rate object. We run it again and discover that the Rate object requires a Task object. Following the errors leaves us with the following setup code:

1 2 3 4 | let(:client) { Client.create! }let(:project) { Project.create!(client: client) }let(:task) { Task.create!(:task, project: project) }let(:user) { User.create!(email: 'user@example.com', password: 'password') } |

Once the setup objects are put together, the test passes!

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | require 'rails_helper'describe TimeEntriesController do let(:client) { Client.create! } let(:project) { Project.create!(client: client) } let(:task) { Task.create!(:task, project: project) } let(:user) { User.create!(email: 'user@example.com', password: 'password') } describe '#send_entries' do it 'delivers an email' do time_entry = TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: Time.current, actual_end_time: Time.current, task: task, user: user) post :send_invoice last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description end end |

Whenever you get a test passing, you want to ensure that the test can also fail. The condition to make the test fail is to get the time entry’s #actual_start_time attribute outside of the range of the query. For the sake of simplicity, you’ll need to trust me that this test is legitimate.

We can get the other basic tests running, now that we have the setup code in place.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 | it 'delivers an email' do post :send_entries last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.descriptionendit 'flashes a success message' do post :send_entries expect(flash[:success]).to eq("Time Entries were successfully sent to you.")endit 'redirects to root path' do post :send_entries expect(response).to redirect_to(root_path)end |

We go through this cycle of setting up the skeleton of the test and letting the failures guide us to a green test for the rest of the pending tests. The test code ends up being 113 lines. I’ll post it here for completion’s sake, but understanding the process of getting the pending tests passing is the core idea of the bootstrapping section.

001 002 003 004 005 006 007 008 009 010 011 012 013 014 015 016 017 018 019 020 021 022 023 024 025 026 027 028 029 030 031 032 033 034 035 036 037 038 039 040 041 042 043 044 045 046 047 048 049 050 051 052 053 054 055 056 057 058 059 060 061 062 063 064 065 066 067 068 069 070 071 072 073 074 075 076 077 078 079 080 081 082 083 084 085 086 087 088 089 090 091 092 093 094 095 096 097 098 099 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 | require 'rails_helper'describe TimeEntriesController do let(:client) { Client.create! } let(:project) { Project.create!(client: client) } let(:task) { Task.create!(:task, project: project) } let(:user) { User.create!(email: 'user@example.com', password: 'password') } before do sign_in(user) end describe '#send_entries' do let(:yesterday) { Time.current - 1.day } let(:tomorrow) { Time.current + 1.day } let!(:time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: Time.current, actual_end_time: Time.current, task: task, user: user) end let!(:yesterday_time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: yesterday, actual_end_time: Time.current, task: task, user: user, description: 'Time Entry From Yesterday') end let!(:tomorrow_time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: tomorrow, actual_end_time: tomorrow + 1.day, task: task, user: user, description: 'Time Entry From Tomorrow') end it 'delivers an email' do post :send_entries last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description end it 'flashes a success message' do post :send_entries expect(flash[:success]).to eq("Time Entries were successfully sent to you.") end it 'redirects to root path' do post :send_entries expect(response).to redirect_to(root_path) end context 'start date is present' do let(:query_params) do { start_date: yesterday } end context 'end date is present' do before do query_params.merge!(end_date: tomorrow) end it 'sends time entries between start date and end date' do post :send_entries, query_params last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description expect(last_email).to have_content yesterday_time_entry.description expect(last_email).to have_content tomorrow_time_entry.description end end context 'end date is not present' do before do query_params.merge!(end_date: nil) end it 'sends entries between start date and today' do post :send_entries, query_params last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description expect(last_email).to have_content yesterday_time_entry.description # The tomorrow time entry is not in the query range expect(last_email).not_to have_content tomorrow_time_entry.description end end end context 'start date is not present' do let(:query_params) do { start_date: nil } end context 'end date is present' do before do query_params.merge!(end_date: tomorrow) end it 'sends entries between today and end date' do post :send_entries, query_params last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description # The yesterday time entry is not in the query range expect(last_email).not_to have_content yesterday_time_entry.description expect(last_email).to have_content tomorrow_time_entry.description end end context 'end date is not present' do before do query_params.merge!(end_date: nil) end it 'sends entries only from today' do post :send_entries, query_params last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description # Both the tomorrow and yesterday time entries are not in the query range expect(last_email).not_to have_content yesterday_time_entry.description expect(last_email).not_to have_content tomorrow_time_entry.description end end end endend |

We are now completely safe to refactor.

The Extraction Phase

When you have full coverage, refactor aggressively down to the models or extract plain Ruby objects.

We have complete coverage of our controller action. We can now extract the query logic into its own class.

Reading the controller code, there are three main concepts in the time entry query. We have a start_date, end_date, and time_entries. Those three concepts are going to guide the API of the TimeEntryQuery class.

Start with writing the code you’d love to have. You have a full battery of tests behind you, so you are completely safe.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | class TimeEntriesController < ApplicationController def send_entries time_entries = TimeEntryQuery.new(start_date: params[:start_date], end_date: params[:end_date]).time_entries UserMailer.send_time_entries(current_user, time_entries).deliver_now flash[:success] = "Time Entries were successfully sent to you." redirect_to root_path endend |

The code we’d like to have will pass the parameters into a new TimeEntryQuery object and then calls the #time_entries method to perform the actual query.

Our TimeEntryQuery class will look like the following, with all the controller tests still passing:

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | class TimeEntryQuery attr_reader :start_date, :end_date def initialize(start_date: nil, end_date: nil) @start_date = parse_date(start_date) @end_date = parse_date(end_date) end def time_entries TimeEntry.order("actual_start_time DESC") .where("(actual_hours IS NOT NULL OR bill_amount IS NOT NULL) AND actual_start_time >= ? AND actual_start_time <= ?", start_date.beginning_of_day, end_date.end_of_day) end private def parse_date(date) if date Date.parse(date) else Time.zone.today end endend |

The magic sauce happens in the #initialize method. If either the :start_date or the :end_date don’t get specified or are nil, then the query defaults to today Time.zone.today.

The date parsing lives in a private #parse_date method, because the API of this TimeEntryQuery class should only return TimeEntry objects with the #time_entries method and do nothing else. You can set (or not set) :start_date and :end_date at your leisure and perform a query based off of them. That’s what our little class here does!

With our tests passing and our code refactored, let’s call the query from inside the mailer and fulfill our destiny!

With our refactored query, the mailer only sees a super small surface area into how the TimeEntryQuery works. We can reuse our query code anywhere in the application, our email gets delivered in the background, and our mailer method remains super lean!

We’ve got one more step to go.

The Test Refactor Phase

Refactor your controller integration tests into unit tests

Our controller tests no longer need to account for all the edge cases, like having a :start_date param but not having an :end_date param. All of the edge cases are being handled by the TimeEntryQuery class.

Refactoring our controller tests down to the TimeEntryQuery class will help document our new class. As a bonus, we’ll get faster tests since unit tests are faster than controller integration tests.

The tests for our TimeEntryQuery class end up being aesthetically pleasing.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 | require 'rails_helper'describe TimeEntryQuery do let(:client) { Client.create! } let(:project) { Project.create!(client: client) } let(:task) { Task.create!(:task, project: project) } let(:user) { User.create!(email: 'user@example.com', password: 'password') } describe '#time_entries' do let(:yesterday) { Time.current - 1.day } let(:tomorrow) { Time.current + 1.day } let!(:time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: Time.current, actual_end_time: Time.current, task: task, user: user) end let!(:yesterday_time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: yesterday, actual_end_time: Time.current, task: task, user: user, description: 'Time Entry From Yesterday') end let!(:tomorrow_time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: tomorrow, actual_end_time: tomorrow + 1.day, task: task, user: user, description: 'Time Entry From Tomorrow') end context 'start date and end date are supplied' do subject { described_class.new(start_date: yesterday.to_s, end_date: tomorrow.to_s).time_entries } it 'returns time_entries between start date and end date' do expect(subject).to include time_entry expect(subject).to include yesterday_time_entry expect(subject).to include tomorrow_time_entry end end context 'only start date is present' do subject { described_class.new(start_date: yesterday.to_s).time_entries } it 'returns time_entries between start date and today' do expect(subject).to include time_entry expect(subject).to include yesterday_time_entry expect(subject).not_to include tomorrow_time_entry end end context 'only end date is present' do subject { described_class.new(end_date: tomorrow.to_s).time_entries } it 'returns time_entries between today and end date' do expect(subject).to include time_entry expect(subject).not_to include yesterday_time_entry expect(subject).to include tomorrow_time_entry end end context 'no start date and no end date' do subject { described_class.new.time_entries } it 'returns time_entries from today' do expect(subject).to include time_entry expect(subject).not_to include yesterday_time_entry expect(subject).not_to include tomorrow_time_entry end end endend |

Our controller tests get leaned out and explicitly describe the goal of the controller action now, free of edge cases.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 | require 'rails_helper'describe TimeEntriesController do let(:client) { Client.create! } let(:project) { Project.create!(client: client) } let(:task) { Task.create!(:task, project: project) } let(:user) { User.create!(email: 'user@example.com', password: 'password') } before do sign_in(user) end describe '#send_entries' do let(:yesterday) { Time.current - 1.day } let(:tomorrow) { Time.current + 1.day } let!(:time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: Time.current, actual_end_time: Time.current, task: task, user: user) end let!(:yesterday_time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: yesterday, actual_end_time: Time.current, task: task, user: user, description: 'Time Entry From Yesterday') end let!(:tomorrow_time_entry) do TimeEntry.create!(actual_start_time: tomorrow, actual_end_time: tomorrow + 1.day, task: task, user: user, description: 'Time Entry From Tomorrow') end it 'delivers an email' do post :send_entries last_email = ActionMailer::Base.deliveries.last expect(last_email).to have_content time_entry.description end it 'flashes a success message' do post :send_entries expect(flash[:success]).to eq("Time Entries were successfully sent to you.") end it 'redirects to root path' do post :send_entries expect(response).to redirect_to(root_path) end endend |

Wrapping Up

Rails controllers have multiple responsibilities and integrate all of the code in your application. This makes them a breeding ground for untested, bad code.

This article prescribes a blueprint for wrangling legacy controller code:

- Wrap controller code with pending tests to gain understanding.

- Write out the tests. Let test failures guide you to green tests.

- When you have full coverage, refactor aggressively down to the models or extract plain Ruby objects.

- Refactor your controller integration tests into unit tests.

Armed with these steps, you can wrap your mind around unknown codebases, get them under test, and refactor safely.

You can read the commits of this article’s code refactor on GitHub.

| Reference: | Refactoring Legacy Rails Controllers from our WCG partner Joshua Plicque at the Codeship Blog blog. |