Replacing Sinatra with Rack in Sidekiq

Sidekiq is one of the first gems that I install when doing a significant Rails project. If you plan to or already have Redis running, it provides an almost effortless ability to process background jobs.

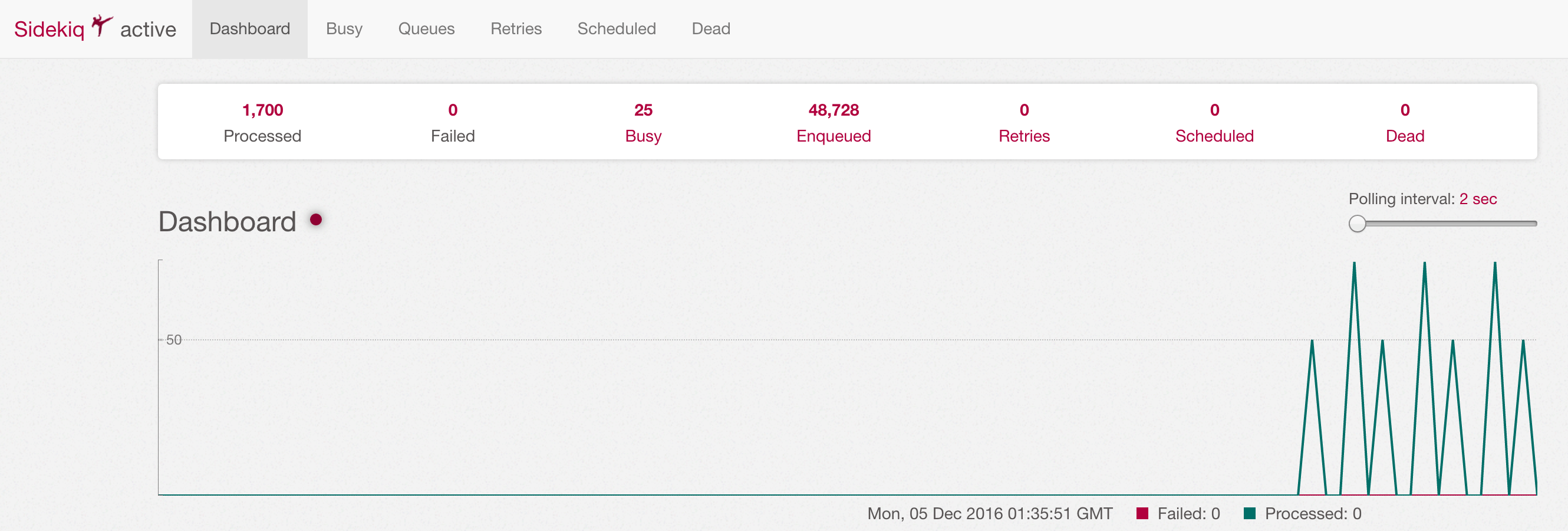

Aside from that, I’ve always thought that one of the most powerful components of Sidekiq was the web UI that it ships with.

Prior to Sidekiq 4.2, the Web UI was implemented as a Sinatra app that you could mount inside of your Rails app. This worked great with Rails 4, but when the Rails 5 release was being prepped there were some issues with the latest release of Sinatra.

Amadeus Folego began working on the large task of seeing if it would be possible to actually remove Sinatra as a dependency of Sidekiq.

In this article, we’re going to take a look at what Rack is and how to deploy a minimal Rack app to Heroku. Then we’re going to look deeper into a few of the things involved in making this transition possible, from Sinatra to a pure Rack app for the Sidekiq Web UI.

What Is Rack

Rack is an interface between web servers that support Ruby (Puma, Thin, Unicorn, Phusion Passenger) and Ruby web frameworks. All of the major Ruby web frameworks (Rails, Sinatra, Hanami, etc…) are built on top of Rack. They are what you would call Rack apps.

The basic premise of Rack is that you must provide the run method something which responds to call. This could be a class with a self.call method, or it could be a Proc. This method must return an array containing three items: [Status Code, Hash of headers, Array of content strings].

Let’s set up our Gemfile:

source 'https://rubygems.org' gem 'rack'

And put the following code inside of a file named config.ru. If you would like to run this app locally, you can with the command rackup config.ru and visit it in your browser using the port that is shown in the terminal.

class App

def self.call(env)

[200, {'Content-Type' => 'text/html'}, ["Hello Rack."]]

end

end

run AppNow to test that it works:

➜ rackapp git:(master) ✗ curl localhost:9292 Hello Rack.%

This can easily be deployed to Heroku without changing anything at all. Heroku knows how to deal with Rack-based Ruby applications; Heroku has an article which goes into further details about hosting Rack applications on their platform.

The Sidekiq Web UI

Rails routes allow you to “mount” any Rack app onto a path, and this is what you’re doing when you mount the Sidekiq Web UI into your Rails app:

require 'sidekiq/web' mount Sidekiq::Web => '/sidekiq'

Prior to Sidekiq 4.2, when you ran this code, what you were doing was mounting a Sinatra app inside of your Rails app. Again, the reason you can do this is because both of these frameworks are built on top of Rack and therefore conform to the same standards.

Although Sinatra is nowhere near the same size and complexity as Rails, any dependency that you introduce to your application is a balance between the costs and benefits. The benefits are easy, in this case we were getting a lightweight web framework that Sinatra provides (routing, views, sessions, static files, and more) allowing Sidekiq to include a beautiful web UI.

This was fine for a long time, but when there was an incompatibility between Rails 5 and the most recent version of Sinatra published at the time, Amadeus Folego had the idea of removing Sinatra as a Sidekiq dependency and replacing it with a pure Rack application.

Replacing Sinatra with Rack in Sidekiq

Part of the cost of not using Sinatra is that some of its features had to be reimplemented from scratch. We’ll look at two of them: Routing and Views.

Routing

Routing involves matching an incoming request to the block of code which should handle that request and perform the work that needs to be performed. The main things that are usually matched on are the HTTP methods (get, delete, post, put, patch, head) and the path. To accomplish that, a simple DSL was built to allow the routes to be defined.

get "/queues" do @queues = Sidekiq::Queue.all erb(:queues) end

That looks identical to what you’d see in Sinatra, except that it’s up to us to define the actual get method:

def get(path, █) route(GET, path, █) end

That eventually calls the route method that adds this route to a Hash that contains an Array of routes for each HTTP method.

def route(method, path, █)

@routes ||= { GET => [], POST => [], PUT => [], PATCH => [], DELETE => [], HEAD => [] }

@routes[method] << WebRoute.new(method, path, block)

endSo now that the routes have been defined, there needs to be a way to match an incoming request to the appropriate route.

In the following code, you’ll see that there is an env variable. This is something provided by Rack that contains all the information you’d need to know about the incoming request. That includes things like the query string (e.g., ?page=2), the path /queues, and all of the other headers normally transmitted in an HTTP request.

The routes for the specific HTTP method are looped through and matched using a Regex expression for more complicated paths or a simple String comparison for simple ones like the /queues example above.

When a match is found, a new instance of the WebAction class is returned along with the modified env variable and the block of code associated to that route.

def match(env)

request_method = env[REQUEST_METHOD]

path_info = ::Rack::Utils.unescape env[PATH_INFO]

@routes[request_method].each do |route|

if params = route.match(request_method, path_info)

env[ROUTE_PARAMS] = params

return WebAction.new(env, route.block)

end

end

nil

endViews

We’re halfway there… we’ve found the route that matches the incoming request, and now it’s time to render the view.

Again, because Sinatra isn’t being used, we’re on our own. If we take a look at the route declaration again, you’ll see that an erb method is called, passing which template should be rendered.

get "/queues" do @queues = Sidekiq::Queue.all erb(:queues) end

What’s amazing and sometimes can go unnoticed is the amount of work that library maintainers such as Mike and contributors from the community such as Amadeus put into code optimization and speed. Looking back through the history of this feature, it was very interesting to see the first version of this code and how it evolved along the way.

Version 1 was a bit more naive and involved reading the ERB template file, then rendering the ERB every time the route was requested.

def erb(file)

output = _render { ERB.new(File.read "#{Web::VIEWS}/#{file}.erb").result(binding) }

[200, { CONTENT_TYPE => TEXT_HTML }, [output]]

endYou’ll notice a _render method. This method handles putting the template inside of a layout where the layout has a yield call.

Version 2 made things faster by storing the template inside of a class-level variable. This sped things up by not having to read the file every time.

def erb(content, options = {})

filename = "#{Web.settings.views}/#{content}.erb"

unless content = @@files[filename]

content = @@files[filename] = ERB.new(File.read(filename))

end

content = _erb(content, options[:locals])

_render { content }

end

private

def _erb(file, locals)

locals.each {|k, v| define_singleton_method(k){ v } } if locals

file.result(binding)

endThe final version goes one step further and caches the parsed version of the ERB template into a method on the WebAction class. It uses a metaprogramming method called class_eval which allows you to dynamically run a String of Ruby code on the class.

What this code is doing is defining a new method that contains the compiled version of the ERB template. It will only be defined once, which is what the unless respond_to?(:"_erb_#{content}") line of code is looking for.

You’d end up with a method named _erb_queues using the example we’ve been looking at.

def erb(content, options = {})

unless respond_to?(:"_erb_#{content}")

src = ERB.new(File.read("#{Web.settings.views}/#{content}.erb")).src

WebAction.class_eval("def _erb_#{content}\n#{src}\n end")

end

content = _erb(content, options[:locals])

# render this ERB template within the Layout of the entire Sidekiq Web UI

_render { content }

end

private

def _erb(file, locals)

# define methods for each "local" variable sent along to the ERB template when it is rendered

# because ERB code is run within the context of the current object, it will have access to these

# new methods... {locals: {name: 'Leigh'}} could be called simply with `name` in the view

locals.each {|k, v| define_singleton_method(k){ v } } if locals

# dynamically call the new method which was defined via `class_eval` in the `erb` method above

send(:"_erb_#{file}")

endI’ve simplified the above code examples a little bit to remove some of the additional complexity handled by the actual Sidekiq code, but the outcome of the code is basically the same.

Conclusion

In this article, we looked at how Mike Perham and Amadeus Folego went about making the transition from powering the Sidekiq Web UI with Sinatra to having it powered by a pure Rack app.

We took a look at a couple of the different aspects that are sometimes overlooked because they are handled by a framework but are left up to us if we choose to use Rack without any further help. Specifically we looked at the routing and how the ERB templates were implemented.

Thanks to Mike and Amadeus’ hard work, Sidekiq now has fewer dependencies and outperforms the previous version of the Web UI.

| Reference: | Replacing Sinatra with Rack in Sidekiq from our WCG partner Leigh Halliday at the Codeship Blog blog. |